Tess Newton Cain, Feiloakitau Kaho Tevi

To reboot Pacific Conversations, Tess recently met with Fei Tevi over coffee in Port Vila. You can hear a podcast of their conversation here and read a transcript here. For the highlights of what they discussed, read on…

I started by asking Fei to fill us in on his background and participation to date in development in the Pacific. Fei is now based in Vanuatu as a result of his wife Eleni’s position at the Melanesian Spearhead Group. He is working as a consultant to the governments of Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, assisting them in developing sustainable development policies and brings with him a wealth of experience in diplomacy, international relations and civil society activism and advocacy.

I am trained in diplomacy and international relations. I worked for the churches for a number of years, over a decade, both in Geneva, Switzerland and also here in the Pacific … prior to that, I was with the Pacific Concerns Resource Center, which is the secretariat to the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific Movement. Very formative years, ’96 to 2000.

During 2015, Fei participated in the Pacific Islands Development Forum (PIDF) in Suva and was also in Port Moresby for the Pacific Islands Forum leaders’ meeting. So I was keen to find out what he thought the relative strengths and weaknesses are of those regional groupings. In relation to the Pacific Islands Forum, Fei was quick to acknowledge the leadership input of Dame Meg Taylor and said he was watching with interest to see what the further impacts of that would be. He then told me categorically that he thought the issue of West Papua would be critical for the Pacific Islands Forum in the future:

And so this is what I’m saying. The Forum itself, the issue will be a determining factor how they treat West Papua and how they are able to get the political support around the issue. And it won’t go away.

In relation to the PIDF, Fei felt that it had achieved a significant success in 2015 by providing a space for Pacific island leaders to caucus around key issues, especially a joint position for the COP 21 talks in Paris, ahead of the Forum meeting in Port Moresby:

But I think PIDF had a role to play in harnessing the collective momentum of the countries, to stand together and say, “Yes, this is what we need.” And not to be pulled apart … We had one meeting after the other, and people saying the same things and coming right through and holding their stance at the Forum, saying “This is what we want, and this is what you get.” Despite all the pressures, despite all the checkbook diplomacy, everything was up to try and get the Pacific island countries to shift and take position. And kudos to them.

And then he provided a very important statement to define the role and place of the PIDF; one that I feel has not been so clearly and explicitly articulated before now:

…we need to have clarity on what PIDF is. It’s a space. Maintaining that space is a very difficult challenge. Everybody wants to cloud that space, Fiji included. Everybody wants to get that space, monopolise that space. As long as we can keep that space as an opportunity for people to come and talk about issues or challenges, talk about opportunities, discuss deals, that will form the character of PIDF. It’s not a CROP agency. It will not deliver on water tanks and water and sanitation programs. It’s not geared towards that.

We then moved on to discuss the concept of ‘green growth’ in the Pacific context, which is an aspect of development with which Fei has been very involved in recent years. I began by asking him how he conceptualises the Pacific concept of green growth, given that it appears to be something that has yet to achieve one accepted definition globally:

In the work that we’ve been doing over the last 3-4 years, in the Pacific, green growth has to do with lifestyles; green growth has to do with a sustainable approach to development. Green growth has to do with—the maturity of the countries to determine where and how they want to address development.

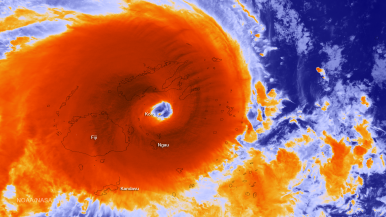

He sees the Pacific conceptualisation of green growth as being one that goes beyond technological interventions. So, next, I asked Fei to give me some sense of what green growth means in a practical sense. How can it or should it influence the way Pacific island countries do business? He took as his starting point the resilience of the communities in Vanuatu further to the impacts of Cyclone Pam last year.

…that for me expresses a set of values that for me green growth encompasses … And that’s part of, I guess, a sense of maturity that we are going through. The recognition that there is something that we can learn and that the future of the region, in terms of green growth, it’s within us. We need to find the tools to identify this and to identify those components of what we can achieve. So that’s one example we can quote. Examples of which time and time again, the resilient nature of these communities has expressed itself with or without help or foreign assistance. So we need to think about that. We need to think how that defines, how that defines growth for us.

Drawing on Fei’s longstanding and extensive involvement with civil society activism in our region, I asked him how he assessed the current capacity within that sector to influence national and regional decision-making about the important issues that we face. He reflected on the changing nature of activism in the region, which he felt had been blunted as a result of becoming ‘institutionalised’ in the 1990s. However, more recently, he had seen resurgence particularly around the issues of self-determination for West Papua and climate change activism:

You have the new environmental activists that are coming through, the young Solwarans, the Young Solwara movement, the Wan Solwara movement, the other groups that have— … PICAN, Pacific Islands Climate Action Network. These are all young, new activists that are coming through.

I expressed a concern that a weakness for civil society at present in our region is a lack of access to and influence with governments. Fei was quite clear that governments in the region should do much more to include civil society in relevant discussions and policy formulation:

… I think we cannot point five of our fingers at civil society. I think there’s a lot of responsibility also that governments have to take on in terms of how they deal with civil society… there has to be a revisiting of what civil service means, and being a civil servant. You are a servant of the government, and by government means the people. So you serve the people. It’s not the other way around. The people don’t come in on their knees to come and ask for service. They shouldn’t. Citizens, rightfully, ask and request their assistance, and their service. Then I think there needs to be a give and take in this discussion.

Finally, we discussed the impact of the election of ‘Akilisi Pohiva as prime minister of Tonga and what it means for democracy in that country. He was quick to acknowledge that the early months have proved disappointing in some ways:

I think in the longer run, in the medium to long term, I think there’s a lot of benefit that can accrue from ‘Akilisi and his time, and his government being in place. I think there’s a lot of lessons that can be taken from the first year or so of ‘Akilisi’s government. A lot of questionable decisions.

He then went on to make a very interesting observation in relation to what we can expect from Tonga in terms of regional participation:

There is more good than bad—there’s more strengths than weaknesses that’s coming out of this government. The fact that, you know, Tonga has taken a strong stance on the issue of West Papua is a token of that and you will see, you will see this government taking on regional issues in a much more stronger way than in the past. The first year has been about consolidating and shifting the country at the national level. I think you will see Tonga playing a more influential role in the region in the future.

…something to look forward to, for sure.

Tess Newton Cain is a Visiting Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. Fe’iloakitau Kaho Tevi is a consultant to the governments of Solomon Islands and Vanuatu on sustainable development policies, and has experience in diplomacy, international relations and civil society activism and advocacy.