https://www.weforum.org/agenda/authors/ana-swanson, Source: https://www.weforum.org/

It sounds kind of crazy to say that foreign aid often hurts, rather than helps, poor people in poor countries. Yet that is what Angus Deaton, the newest winner of the Nobel Prize in economics, has argued.

Deaton, an economist at Princeton University who studied poverty in India and South Africa and spent decades working at the World Bank, won his prize for studying how the poor decide to save or spend money. But his ideas about foreign aid are particularly provocative. Deaton argues that, by trying to help poor people in developing countries, the rich world may actually be corrupting those nations’ governments and slowing their growth. According to Deaton, and the economists who agree with him, much of the $135 billion that the world’s most developed countries spent on official aid in 2014 may not have ended up helping the poor.

The idea of wealthier countries giving away aid blossomed in the late 1960s, as the first humanitarian crises reached mass audiences on television. Americans watched through their TV sets as children starved to death in Biafra, an oil-rich area that had seceded from Nigeria and was now being blockaded by the Nigerian government, as Philip Gourevitch recalled in a 2010 story in the New Yorker. Protesters called on the Nixon administration for action so loudly that they ended up galvanizing the largest nonmilitary airlift the world had ever seen. Only a quarter-century after Auschwitz, humanitarian aid seemed to offer the world a new hope for fighting evil without fighting a war.

There was a strong economic and political argument for helping poor countries, too. In the mid-20th century, economists widely believed that the key to triggering growth — whether in an already well-off country or one hoping to get richer — was pumping money into a country’s factories, roads and other infrastructure. So in the hopes of spreading the Western model of democracy and market-based economies, the United States and Western European powers encouraged foreign aid to smaller and poorer countries that could fall under the influence of the Soviet Union and China.

The level of foreign aid distributed around the world soared from the 1960s, peaking at the end of the Cold War, then dipping before rising again. Live Aid music concerts raised public awareness about challenges like starvation in Africa, while the United States launched major, multibillion-dollar aid initiatives. And the World Bank and advocates of aid aggressively seized on research that claimed that foreign aid led to economic development.

Deaton wasn’t the first economist to challenge these assumptions, but over the past two decades his arguments began to receive a great deal of attention. And he made them with perhaps a better understanding of the data than anyone had before. Deaton’s skepticism about the benefits of foreign aid grew out of his research, which involved looking in detail at households in the developing world, where he could see the effects of foreign aid intervention.

“I think his understanding of how the world worked at the micro level made him extremely suspicious of these get-rich-quick schemes that some people peddled at the development level,” says Daron Acemoglu, an economist at MIT.

The data suggested that the claims of the aid community were sometimes not borne out. Even as the level of foreign aid into Africa soared through the 1980s and 1990s, African economies were doing worse than ever, as the chart below, from a paper by economist Bill Easterly of New York University, shows.

William Easterly, “Can Foreign Aid Buy Growth?”

The effect wasn’t limited to Africa. Many economists were noticing that an influx of foreign aid did not seem to produce economic growth in countries around the world. Rather, lots of foreign aid flowing into a country tended to be correlated with lower economic growth, as this chart from a paper byArvind Subramanian and Raghuram Rajan shows.

The countries that receive less aid, those on the left-hand side of the chart, tend to have higher growth — while those that receive more aid, on the right-hand side, have lower growth.

Raghuram G. Rajan and Arvind Subramanian, “Aid and Growth: What Does the Cross-Country Evidence Really Show?”

Raghuram G. Rajan and Arvind Subramanian, “Aid and Growth: What Does the Cross-Country Evidence Really Show?”Why was this happening? The answer wasn’t immediately clear, but Deaton and other economists argued that it had to do with how foreign money changed the relationship between a government and its people.

Think of it this way: In order to have the funding to run a country, a government needs to collect taxes from its people. Since the people ultimately hold the purse strings, they have a certain amount of control over their government. If leaders don’t deliver the basic services they promise, the people have the power to cut them off.

Deaton argued that foreign aid can weaken this relationship, leaving a government less accountable to its people, the congress or parliament, and the courts.

“My critique of aid has been more to do with countries where they get an enormous amount of aid relative to everything else that goes on in that country,” Deaton said in an interview with Wonkblog. “For instance, most governments depend on their people for taxes in order to run themselves and provide services to their people. Governments that get all their money from aid don’t have that at all, and I think of that as very corrosive.”

It might seem odd that having more money would not help a poor country. Yet economists have long observed that countries that have an abundance of wealth from natural resources, like oil or diamonds, tend to be more unequal, less developed and more impoverished, as the chart below shows. Countries at the left-hand side of the chart have fewer fuels, ores and metals and higher growth, while those at the right-hand side have more natural resource wealth, yet slower growth. Economists postulate that this “natural resource curse” happens for a variety of reasons, but one is that such wealth can strengthen and corrupt a government.

Like revenue from oil or diamonds, wealth from foreign aid can be a corrupting influence on weak governments, “turning what should be beneficial political institutions into toxic ones,” Deaton writes in his book “The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality.” This wealth can make governments more despotic, and it can also increase the risk of civil war, since there is less power sharing, as well as a lucrative prize worth fighting for.

Deaton and his supporters offer dozens of examples of humanitarian aid being used to support despotic regimes and compounding misery, including in Zaire, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Somalia, Biafra, and the Khmer Rouge on the border of Cambodia and Thailand. Citing Africa researcher Alex de Waal, Deaton writes that “aid can only reach the victims of war by paying off the warlords, and sometimes extending the war.”

He also gives plenty of examples in which the United States gives aid “for ‘us,’ not for ‘them’” – to support our strategic allies, our commercial interests or our moral or political beliefs, rather than the interests of the local people.

The United States gave aid to Ethiopia for decades under then-President Meles Zenawi Asres, because he opposed Islamic fundamentalism and Ethiopia was so poor. Never mind that Asres was “one of the most repressive and autocratic dictators in Africa,” Deaton writes. According to Deaton, “the award for sheer creativity” goes to Maaouya Ould Sid’Ahmed Taya, president of Mauritania from 1984 to 2005. Western countries stopped giving aid to Taya after his government became too politically repressive, but he managed to get the taps turned on again by becoming one of the few Arab nations to recognize Israel.

Some might argue for bypassing corrupt governments altogether and distributing food or funding directly among the people. Deaton acknowledges that, in some cases, this might be worth it to save lives. But one problem with this approach is that it’s difficult: To get to the powerless, you often have to go through the powerful. Another issue, is that it undermines what people in developing countries need most — “an effective government that works with them for today and tomorrow,” he writes.

The old calculus of foreign aid was that poor countries were merely suffering from a lack of money. But these days, many economists question this assumption, arguing that development has more to do with the strength of a country’s institutions – political and social systems that are developed through the interplay of a government and its people.

There are lot of places around the world that lack good roads, clean water and good hospitals, says MIT’s Acemoglu: “Why do these places exist? If you look at it, you quickly disabuse yourself of the notion that they exist because it’s impossible for the state to provide services there.” What these countries need even more than money is effective governance, something that foreign aid can undermine, the thinking goes.

Some people believe that Deaton’s critique of foreign aid goes too far. There are better and worse ways to distribute foreign aid, they say. Some project-based approaches — such as financing a local business, building a well, or providing uniforms so that girls can go to school — have been very successful in helping local communities. In the last decade, researchers have tried to integrate these lessons from economists and argue for more effective aid practices.

Many people believe that the aid community needs more scrutiny to determine which practices have been effective and which have not. Economists such as Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, for example, argue for creating randomized control trials that allow researchers to carefully examine the development effects of different types of projects — for example, following microcredit as it is extended to people in poor countries.

These methods have again led to a swell in optimism in professional circles about foreign aid efforts. And again, Deaton is playing the skeptic.

While Deaton agrees that many development projects are successful, he’scritical of claims that these projects can be replicated elsewhere or on a larger scale. “The trouble is that ‘what works’ is a highly contingent concept,” he said in an interview. “If it works in the highlands of Kenya, there’s no reason to believe it will work in India, or that it will work in Princeton, New Jersey.”

The success of a local project, like microfinancing, also depends on numerous other local factors, which are harder for researchers to isolate. Saying that these randomized control trials prove that certain projects cause growth or development is like saying that flour causes cake, Deaton writes in his book. “Flour ‘causes’ cakes, in the sense that cakes made without flour do worse than cakes made with flour – and we can do any number of experiments to demonstrate it – but flour will not work without a rising agent, eggs, and butter – the helping factors that are needed for the flour to ‘cause’ the cake.”

Deaton’s critiques of foreign aid stem from his natural skepticism of how people use — and abuse — economic data to advance their arguments. The science of measuring economic effects is much more important, much harder and more controversial than we usually think, he told The Post.

Acemoglu said of Deaton: “He’s challenging, and he’s sharp, and he’s extremely critical of things he thinks are shoddy and things that are over-claiming. And I think the foreign aid area, that policy arena, really riled him up because it was so lacking in rigor but also so grandiose in its claims.”

Deaton doesn’t argue against all types of foreign aid. In particular, he believes that certain types of health aid – offering vaccinations, or developing cheap and effective drugs to treat malaria, for example — have been hugely beneficial to developing countries.

But mostly, he said, the rich world needs to think about “what can we do that would make lives better for millions of poor people around the world without getting into their economies in the way that we’re doing by giving huge sums of money to their governments.” Overall, he argues that we should focus on doing less harm in the developing world, like selling fewer weapons to despots, or ensuring that developing countries get a fair deal in trade agreements, and aren’t harmed by U.S. foreign policy decisions.

Deaton also believes that our attitude toward foreign aid – that developed countries ought to swoop in and save everyone else – is condescending and suspiciously similar to the ideas of colonialism. The rhetoric of colonialism, too, “was all about helping people, albeit about bringing civilization and enlightenment to people whose humanity was far from fully recognized,” he has written.

Instead, many of the positive things that are happening in Africa – the huge adoption in cell phones over the past decade, for example – are totally homegrown. He points out that, while the world has made huge strides in reducing poverty in recent decades, almost none of this has been due to aid. Most has been due to development in countries like China, which have received very little aid as a proportion of gross domestic product and have “had to work it out for themselves.”

Ultimately, Deaton argues that we should stand aside and let poorer countries develop in their own ways. “Who put us in charge?” he asks.

This article is published in collaboration with Washington Post. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Ana Swanson is a reporter for Wonkblog specializing in business, economics, data visualization and China.

Image: People carry food aid distributed. REUTERS/Antonio.

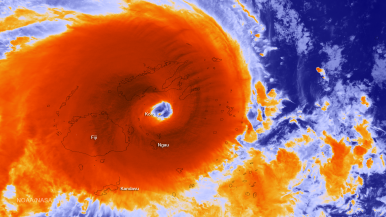

Many of the planet’s most prized destinations, places considered exquisite and idyllic, where nature seems bountiful and people appear at ease, are under threat. In less than a decade, climate change-induced sea level rise could force thousands of people to migrate from some of the world’s 52 small island developing states (Sids).

Many of the planet’s most prized destinations, places considered exquisite and idyllic, where nature seems bountiful and people appear at ease, are under threat. In less than a decade, climate change-induced sea level rise could force thousands of people to migrate from some of the world’s 52 small island developing states (Sids).